Posted October 06th 2017

I will be telling them about servicemen from Ireland who fought at the Western Front in World War I, particularly about young men from Cork and the surrounding area who suffered ‘shell shock’ whilst fighting in the trenches.

‘Shell shock’ was the term used at the time to describe the often profound physical and psychological symptoms that were suffered by many soldiers in the absence of obvious physical injuries. Some of the more enduring cases were sent back to England and admitted to the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic (today the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery) in London.

The case records of this internationally leading hospital have been completely preserved, and also contain the histories of several servicemen from Wales.

Private Llewellyn S.

While in a barn near Ypres, ‘a shell struck the roof, blew it off and set fire to the barn. His two companions in the barn were killed and the large quantity it contained of ammunition began to pop off. He rushed out in a dazed condition, but was able to carry his killed companions in a stretcher for 3 miles to a hospital, where he went sick himself, complaining of pain all up the spine. That night in hospital he ran amok with a rifle and then had a fit.

He felt this coming on; he had a faint feeling and almost at once lost consciousness. He does not know how long he remained so, or what happened in the fit. Since this date he has had frequent headache, loss of memory, rambling in his sleep, and general depression.

This is the story of the breakdown of Llewellyn S. Llewellyn was one of the first soldiers with shell shock to be admitted to the National Hospital. After seven years of military service in India with the 1st Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, this 29-year old Corporal from Cardiff had just returned to England in November 1914.

He was despatched to France straight away and immediately went into action in Flanders. According to his medical records, he – ‘like all the Indian Army, had not felt really fit on account of the weather, but was otherwise well in his general health’. Since being at the front, he had been growing more and more depressed and had ‘caused remarks by his absent-minded ways’.

At the time of Llewellyn’s admission, doctors were still puzzled by the symptoms of soldiers who were physically unscathed, but displayed a wide variety of mainly somatic symptoms. Although Llewellyn had not been injured and presented as a ‘fairly nourished man’ with healthy organs, he had a ‘gaunt weary expression’ and seemed deeply depressed. Except for a fine tremor of his extended hands and a general apathy, he did not show any obvious symptoms of shell shock. After two weeks of general massage, sedatives and light electrical treatment along his spine, he was discharged ‘much improved, but still a rather ‘melancholy Jacques’’.

Image: Shining Angels throw a protective curtain around men from the Lincolnshire Regiment at Mons; Alfred Pearse, published in ‘The chariots of God’ by a churchwoman in 1915, (London AH Stockwell, 1916).

Private John H.

Another shell-shocked soldier from Wales was Private John H. of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, a 25-year old miner from Penygroes in Carmarthenshire. John had left school at 13 to work in one of the mines of the Southern coalfield. He enlisted in February 1916 and was sent to France in April 1917. At Bullecourt, at 5am on May 13th:

John’s unit was ordered to make an attack and he got into the German trenches and preceded about 7 yards when he received a wound in the upper third of his left forearm. There were two scars about 2” long in the back of the arm and a scar about the size of a shilling in the front of the forearm. As soon as he was injured the arm felt helpless; he remained in the trench to about 11 pm before he was taken to a Dressing Station, then to Boulogne where he remained a day. Subsequently, he was transferred to Millbank and then to Tooting Military Hospital six weeks previous to coming to the National.

When he was admitted to Queen Square on 15 March 1918, John’s left arm was paralysed and numb. John had some movement in his elbow, but his wrist and fingers were completely useless. Although he was treated by Ralph Lewis Yealland, one of the most renowned shell shock doctors of his time, the power in John’s left wrist did not fully recover. Like the majority of shell-shocked soldiers treated at the National Hospital, John was discharged from service and never saw the Western Front again.

Llewellyn and John were among the estimated 80,000 British servicemen who suffered shell shock.

Like John, most traumatised soldiers who were admitted to the National Hospital had developed the typical symptoms of shell shock: paralyses, shaking, stuttering, deafness and fits. Others, like Llewellyn, had more subtle posttraumatic symptoms. Llewellyn had developed what psychiatrists today would call ‘dissociative states’, episodes between sleep and wakefulness that enabled the affected individual to keep a certain distance from the outward world.

These soldiers appeared to be absent-minded and detached from their comrades; they often displayed aggressive behaviours, re-enacted battle scenes or wandered away purposelessly. Later on, they did not remember any of their actions. This temporary withdrawal from the horrors of warfare served to protect them from the intense emotional states of fear and helplessness.

While some soldiers slipped in and out of dream-like states, others gradually lost all contact with the real world: they developed strange ideas, behaved in odd ways and had experiences nobody else shared. These psychotic symptoms were not an active, conscious survival or coping strategy: rather, they overwhelmed the individual and replaced reality with an alternative world. Some psychotic states could have a temporary problem-solving and wish-fulfilling function, and serve as an escape from a disturbing life situation.

Karl Jaspers, the German psychiatrist and philosopher, provided the classical account of this phenomenon in his General Psychopathology:

Through delusions and hallucinations the individual’s fears, needs, hopes and wishes seem to become alive and real. […] Reactive psychosis serves as a defence, a refuge, an escape as well as wish fulfilment. It derives from a conflict with reality which has become intolerable.

Some of these psychotic experiences could take an epidemic course – spreading from one soldier to the next. The sightings of the Angels of Mons (depicted in the image above) – a cloud of angelic warriors that appeared at Mons and halted the German advance against a vastly outnumbered British force – were the most famous collective psychotic experience, but many other similar legends of supernatural warriors, magic castles and mysterious clouds developed during the Great War.

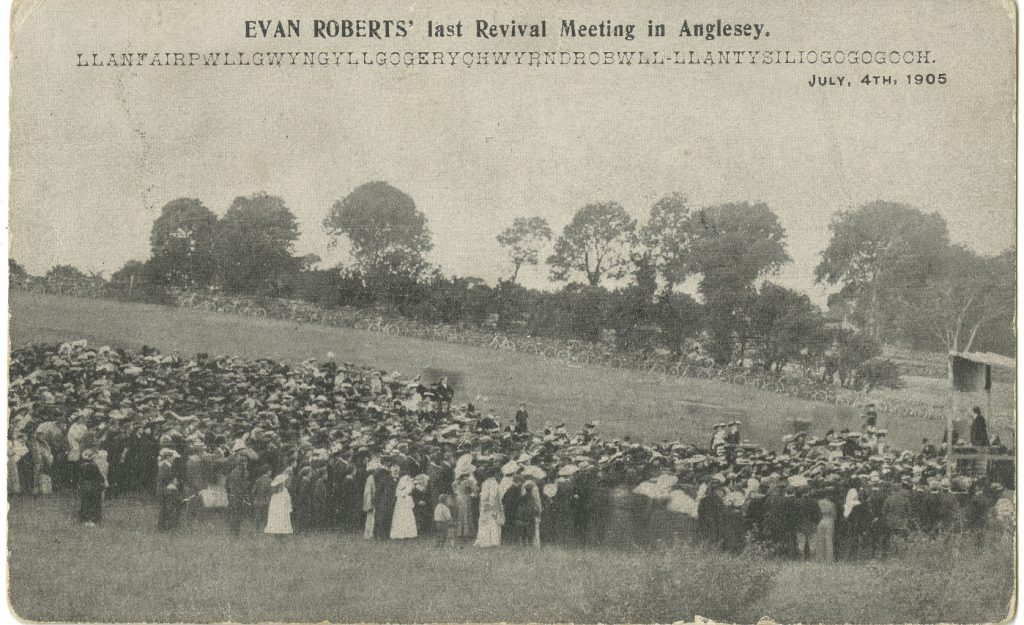

Emotionally charged life events can indeed trigger transient psychotic reactions, as documented in the records of the Denbigh Asylum during the Welsh Religious Revival movement in North Wales in 1904/5, which led to numerous admissions to the Denbigh Asylum.

Image: Anglesey Archives

Challenging traditional thinking

The idea that traumatic experiences could trigger psychotic episodes was very much at odds with traditional psychiatric thinking: psychosis was believed to be a chronic disorder – inevitably leading to intellectual decline and requiring lifelong confinement to a mental institution; yet, many soldiers (and, indeed, the Welsh quarrymen and their wives attending the Religious Revival meetings in North Wales at the beginning of the century) who developed psychotic ideas recovered within a short period of time.

In fact, most people’s concept of psychosis has remained rather monolithic until the present time: there is mental normality on one side and insanity, considered to be a chronic problem, on the other. The cases of shell shock psychosis, and their often impressive recoveries tell another story: life events can trigger psychosis – and although the psychotic illness can, subsequently, take a chronic course, it can also be limited to a single, brief episode. This is only one of many medical lessons from the First World War.

The stories of the traumatised soldiers of the Great War – Welsh, Scottish, English, Irish, American, Australian, Belgian and South African – are retained in the case records of the National Hospital. I have come across similar stories in the medical case records of German and Austrian World War One soldiers.

It is fascinating to enter this world which – since the last veterans of the war have passed away – is now inaccessible through living memory.

All these soldiers whose stories are documented in the medical case records of the time, had witnessed immeasurable suffering, and had been psychologically scarred. Some of them never recovered from their experiences. They were victims of the epidemic of trauma that at some point threatened to overshadow all other medical problems of the war. These individual histories reveal the human condition, the basic human reactions to fear and loss that transcend all political and ideological differences.

Further reading

They Called it Shell Shock: Combat Stress in the First World War

Sign up now and receive new blog posts to your inbox.