Posted September 10th 2016

We often see Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder portrayed by the media as a perfectionistic ailment of sorts: an accumulation of what are regarded to be rather pesky habits that involve excessive tidiness, cleanliness, and a deep desire for the immediate environment to be symmetrically ordered (usually for added comedic value).

These depictions, however, serve to raise awareness of OCD in completely the wrong way by perpetuating and reinforcing myths about the condition.

By reducing OCD to a series of annoying habits, it further stigmatises those with the disorder and as such can lead to increased alienation and isolation.

To tackle some of these common misconceptions around OCD, a good place to start would be by debunking some of the popular myths out there that we’ve all come across at some point.

This is a topic that’s very close to my heart for both professional and personal reasons, as I spent most of my doctoral and post-doctoral years investigating OCD.

I was also diagnosed with OCD when I was 16, a statement I find that most people don’t fully understand at times given the way that the condition is portrayed.

So, instead of focusing exclusively on what the research has shown us over the past few decades, I’m concentrating on the myths from comments by people who are interested in what it means to have OCD but don’t quite know what it implies.

Being open about personal experiences always involves a sense of vulnerability, by addressing some of the common myths and misconceptions we can ease vulnerability and apprehension that many people with this condition may experience.

Myth 1: “I’m a bit OCD”

This is a statement I’ve come across countless times, in both personal and professional settings. While the person making the comment usually has good intentions and tries to put the person with OCD at ease by stating this, it is the very attempt to normalise the distress and anguish associated with the condition that can be particularly damaging.

The media is famous for this particular myth as well, with celebrities for instance describing the strict organisation and categorisation of their sock drawer as ‘OCD’.

Yes, it is possible to have traits that may resemble obsessive-compulsive behaviour but unless these traits and behaviours cause considerable mental and physical distress that go on to impair functioning, it isn’t OCD. No one can be, “a bit OCD” in the same way that you can’t have “a bit” of diabetes. There is much more going on behind what is visible.

Myth 2: You must be a neat freak who enjoys cleaning

Clearly these people haven’t seen my apartment by Thursday during a normal working week.

The problem with this myth is that it insinuates that someone with OCD derives a form of pleasure by performing a compulsive ritualistic act, and that is so wrong for a number of reasons.

OCD is complex in itself and has been considered by some to be an umbrella term for a number of symptom-dimensions that fall under this all-encompassing term.

Washing/cleanliness is one of these ‘types’ of OCD, and probably the one that the media focuses on the most. People with this kind of OCD find no pleasure in having to clean repeatedly, the compulsive cleaning behaviour is the result of distressing thoughts or images (obsessions) that are so aversive and unpleasant that the only way to provide temporary relief from the anguish of the mental event is by performing the ritual.

It’s the acquisition and maintenance of this behaviour in response to these thoughts or images that’s problematic because this temporary relief serves to strengthen the compulsive behaviour, which in essence is an attempt to avoid the presence of that very unpleasant thought or image. This leads to a cycle that becomes increasingly difficult to break.

Performing the behaviour is very distressing, time-consuming, and can interfere with daily life to such an extent that people start to drop out of school or lose their jobs.

This is similar for those with an order-symmetry ‘type’ of OCD. Ordering takes place in order to provide relief, which is always temporary and never permanent. The same applies for other types of OCD such as checking and ‘Pure-O’, whereby the person performs a series of mental acts to neutralise an unpleasant thought, idea, or image.

Myth 3: Can’t you just ignore the thoughts, images, or ideas?

If we could then there would be no need for OCD Awareness Week. Unfortunately, it’s the very intrusive and aversive nature of these thoughts that add to the complexity of the condition.

We all experience bad thoughts, yet people with OCD add importance and are judgemental to these thoughts when they experience them despite acknowledging (in most cases) that the thoughts are not realistic or logical.

What we see in the brains of people with OCD is that there is dysregulation of a particular circuitry that involves regions of the brain that play an important role in emotional processing, reward and reinforcement, and decision making.

As a result, information doesn’t flow the way it usually does in people without OCD symptoms, with a part of the brain responsible for the transfer of this information, so to speak, getting ‘jammed’.

This makes sense considering the way in which people with OCD interpret these thoughts or images, and the excessive guilt and over-responsibility they feel for merely having these thoughts. And the more distressing the thought, the stronger the urge to perform the behaviour that will provide some short-term relief becomes.

It might be easier then to view these kinds of thoughts that people with OCD experience as a kind of mental shock, obviously you can’t ignore an electric shock and you will do whatever you can to turn it off.

In the case of OCD, however, the more you look for arbitrary ways that may temporarily stop the shock, the more likely it is for this shock to increase in intensity and duration the next time, and again you fall into the vicious cycle of trying to switch it off by generating rules of behaviour that may help temporarily.

Myth 4: It’s just stress related, it will pass

Here we need to distinguish between normal stress and abnormal stress. OCD is considered to be an anxiety disorder, which implies that people with OCD don’t experience stress in the same way that most people do.

Usually we all experience stress when we feel that there is some sort of threat to us, very useful for our ancestors in the savannah. This response, however, is exaggerated in people with anxiety disorders, and can occur without any sign of an external physical threat.

Not only can an internal event initiate the stress response but the resistance with which it is met is exhausting, and over time can lead to many other mental and physical problems too.

When anxiety peaks in OCD, the urge to perform the ritualistic compulsive behaviour is at its strongest because of the need to reduce the heightened anxiety being experienced, at least temporarily. Unless treated, OCD will never pass but actually become much worse and more debilitating.

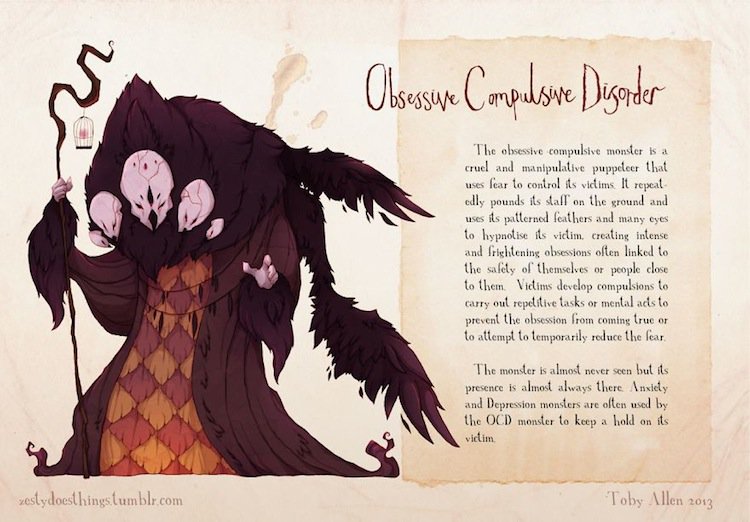

The OCD monster, as depicted by artist Toby Allen.

Myth 5: There is no treatment for OCD

Our understanding and treatment of OCD has come a long way. While there is currently no cure, treatment has been found to be very effective in reducing the impact of the symptoms on the daily lives of people with the condition.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), or more specifically a type of CBT known as Exposure Response Prevention (ERP), is the first line of treatment that has produced amazing results in addressing not only the repetitiveness of the compulsive acts by modifying and strengthening non-avoidance behaviours, but also focuses on decreasing the distress associated with the thoughts, images, ideas or ruminations that are at the centre of the individual’s experience of OCD.

Medication has also been proven to be effective in more moderate and severe cases, alongside CBT.

Two-thirds of people with OCD will go on to improve, however many people struggle for years before a diagnosis of OCD is actually made, mostly because awareness has historically been so poor that people could not identify the signs and symptoms in their loved ones.

Early intervention is therefore a critical part of OCD Awareness Week, one of many ways in which we can all help to lessen the impact of OCD on people who are afflicted with this condition.

Sign up now and receive new blog posts to your inbox.