Posted November 12th 2021

Please note that this blog contains references to suicide.

To this day, I don’t know why it happened.

I was in a loving marriage, well off with a successful, if stressful, career, and I had only a few worries about loved ones and friends, but no more than most people experience.

Yet, at the end of 2018, I suffered a severe psychotic episode and attempted to take my life on numerous occasions.

Those attempts included trying to run into traffic, smuggling car keys away and driving off recklessly, and taking an overdose.

I felt like a lost cause

My family tried to look after me at home and one of my brothers moved back in with me and my husband.

But the overdose, which put me in A&E, proved that even when keeping an eye on me every day, they weren’t able to keep me safe.

I was observed in A&E by the mental health liaison worker who spoke with me and my family.

After discussion with the lead consultant, I was held under Section 3, which legally puts patients in the care and treatment of mental health professionals, for six months.

Hazy memories of hospital

I can remember very little of that time on the ward.

Interactions with patients and staff were very difficult as I was convinced that everyone was there to spy on me. I’d scribble notes down and pass them to my family at visits.

I’ve since seen some of these notes and cannot decipher the incoherent ramblings. They are so foreign to me that I feel they were written by someone else.

On the ward I was given a variety of drugs, none of which had any significant impact on my mental wellbeing, but after a month or so, I was allowed accompanied leave with nurses or family.

During one particularly fraught afternoon out with my husband and my father at a local coffee shop I became severely agitated, banging my head against a table and screaming and shouting that I didn’t want to go back to the ward.

After much gentle persuasion and comforting, I eventually was driven back to the ward with my husband holding me so that I wouldn’t try leaping out of the car.

Even after explaining to the staff how I’d been that afternoon and that I should be supervised, I was allowed out the following day for my first 15 minutes’ unaccompanied release.

I walked out of the hospital grounds to the major road that was adjacent. I sat for some time, with my mind churning over what was happening and – I can’t remember what triggered it – I ran between the parked cars and in front of an oncoming vehicle.

I don’t know if I was just lucky or the driver had fantastic reactions, but I ended up with “just” a broken leg.

I was taken to an A&E department at a different hospital and had my leg operated on and an external fixator cage fitted.

It was at this point that I was given a 24 hours nurse from the mental health ward and they would watch over me continuously.

Trial, error and ECT

More drugs were tried and dosages varied to try and elicit any sort of improvement but to no avail.

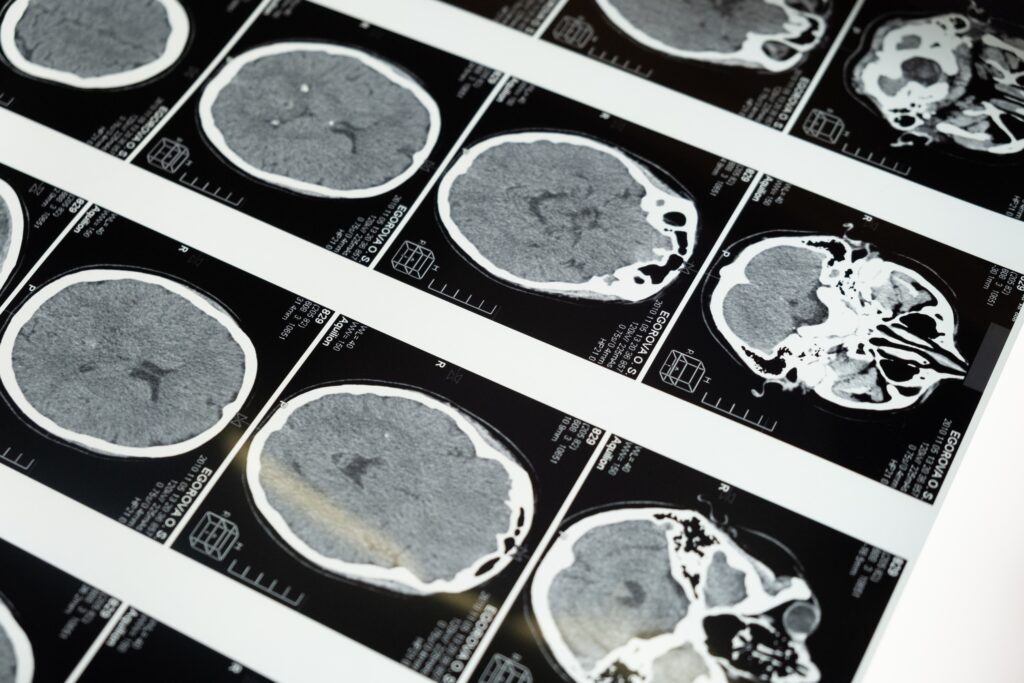

Towards the end of January 2019, the idea of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was suggested by a multidisciplinary team (MDT).

I think the reason I didn’t argue or try to dismiss this treatment was simply that nothing else had worked, so my paranoia was convinced that nothing would.

My family were sceptical about ECT but were more reassured after talking with my consultant and the research my brother did on this subject.

Both of them advised that although the reasons behind the benefits are not clear, the fact that it’d significantly helped many people in my situation was more than enough reason to try.

There was still a worry that as the ECT must be given by patient consent, I would change my mind and decide not to undergo the treatment, but in February 2019 I signed the consent form and was taken over to the elective treatment rooms for the first of twelve sessions.

ECT treatment begins

I can’t remember anything about any of the treatments, but the overwhelming feeling was ‘refreshed’ when the anaesthetic wore off. I’d sleep a lot afterwards.

The Tuesday after my first treatment was my husband’s birthday, and he still says that it was the greatest birthday present he’s ever had, that after being buzzed into the ward, I saw him, gave him a big smile and stood up from my wheelchair and gave him a hug.

Tears still well up in him when he tells me that story. That evening was the first time he saw a glimpse of the person I used to be.

Everyone says the change in me was almost immediate. After being confrontational and abusive with the staff, patients and other visitors, I began to engage with everyone.

My job is in the hospitality sector, so I’ve never had any problem with talking and getting on with people and now they were finally able to see the real me.

I still had moments of darkness, but they were few and far between and became rarer as my treatments every Monday and Thursday progressed.

It was around four sessions that I was granted leave from the ward. Initially, I went out with family for a coffee and a bite, but then eventually unaccompanied.

During this unaccompanied leave, I’d often take requests from other patients on the ward to pick them up newspapers, cigarettes or snacks from the garage down the road, the same road I ran out into three months earlier.

My treatments ended after the tenth session as it was felt that I had benefited from the ECT as much as I could.

In early April I also got a fantastic birthday present myself when my consultant signed me off to cancel my Section 3. I was able to curl up in my own bed for the first time in six months.

I wish I knew why ECT works or how it does, maybe it was just a trigger to allow my brain to let the other drugs do their work, but it has given me back my life, and although I’ve made a lot of changes to look after my mental health, I credit ECT with giving me the chance to get better.

Read more

- NCMH blog | Gwyneth’s experience: Electroconvulsive therapy – friend or foe?

- NCMH blog | Learning more about ECT

- NCMH blog | Mental health stigma and ECT

- NHS | Treatments for depression including Electroconvulsive Therapy

- Shocked: insider stories about electroconvulsive therapy – a book by Prof George Kirov

Sign up now and receive new blog posts to your inbox.